This essay will be

discussing the new wave of craft, primarily knitting, and its meaning in

contemporary art and advertising. The rise in popularity of the handmade and

its commercial knock on effect will be explored, proving the morals behind

modern adverts do not reflect on those of traditional Arts and Crafts, but only

imitate associated stereotypes. With more people returning to the craft of knitting

as well as a youthful following, a community of consumers has formed who are

more aware of mass production and the loss of uniqueness in products. Despite

the growth in the number of crafters, through conventions, social networking

and knitting circles does advertising reflect the principles of craft or play

to a negative stereotype to appeal to a mass audience?

The essay will be

divided into two sections, craft in cotemporary art, and craft in advertising,

each concentrating on the reasons behind the use of the handmade and what that

means in terms of their construction and semiotic value. The first part examines

the Arts and Crafts movement and how contemporary art echoes the values

established by William Morris. Investigating artists that use craft to make a

statement. Elaine Reichek, Barb Hunt, Shauna Richardson and Margi Geerlinks

work will be studied to understand the meaning of craft in art, as well as

theorists such as Anscombe and Gere, and Williamson. The second will analyse recent

advertising campaigns that use knitting as a dominant feature to sell

mass-produced products. The examination of adverts for Shreddies, Sudafed,

Natural Gas and Smirnoff and Cola will prove how advertising is only using the

craft because of its rise in popularity. Both sections will investigate not

only the meaning of craft in each area, but its use of semiotic discourse and

history.

Craft

in Contemporary Art

The new wave of craft

began in the early 1990s, rebelling against the digital process that many

artists were incorporating within their practices. Craft’s renaissance had

begun, contemplating many of the original principles of The Arts and Crafts

movement. Wagner (2008, p1) writes ‘craft is not simply about making but about

making a political statement’ reflecting on John Ruskin and William Morris and

their development of arts political value.

The 19th century saw a new way of making art, a

movement was established ‘as a reaction against the industrial revolution in

hopes of returning society to a simpler way of life’ Hardy-Moffat (n.d.)

states. Led by Morris, the Arts and

Crafts movement combined its own aims with the awareness that a nations art

symbolised the moral values of its society.

Although Britain’s industrialism was leading in Europe there was a need

for art to be restored, ‘an English art for England’ Anscombe and Gere (1978,

p7) write, explaining the need for something new, a reaction against the issues

affecting Victorian England.

|

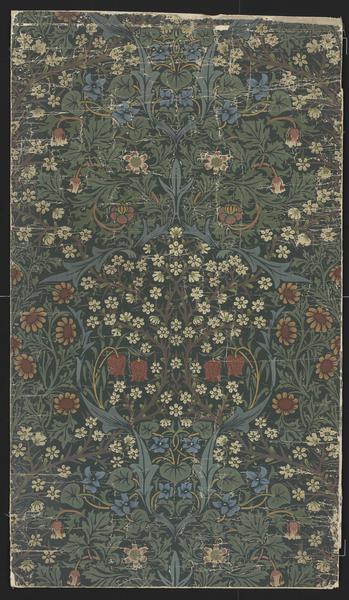

| Fig. 1 |

‘The Arts and Crafts

movement was an attempt to raise design standards at every level’ writes

Greensted (2005, p 4), focusing on education and Morris’ four founding principles

that Hardy-Moffat (n.d.) examines as ‘unity in design, joy in labour,

individualism and regionalism’. These four elements teach that the work

produced must always be considerate of the values behind the movement,

acknowledging the work’s aesthetics should directly parallel its reason for

being. Equal credit would be given to both designer and maker of the piece, for

example fig. 1 gives credit to Morris & Co. for publishing and Jeffery for

printing, establishing a fair relationship throughout the whole process,

Hardy-Moffat (n.d.) writes how this ‘served to minimize the division of labour

imposed by the industrial revolution’. The pieces were original and unique,

protesting mass production using nature as a source for inspiration rebelling

against the advancements in machine technology that factories were

incorporating.

The success of the

movement meant Britain had become a leader in design development and production

with its art; Anscombe and Gere (1978, p47) write ‘Its real aims were to

educate people to an awareness that craft and the craftsman were worthy of

protection’ which is to this day apparent through its legacy and revival. Reflecting on this movement the new wave of

craft can easily be associated with its reasoning. As Morris and Ruskin were

rebelling against the industrial revolution and the replacement of worker with

machine, contemporary artists also considering the rise of technology, Hung and

Magliaro (2007, p11) write

While the

fictionalized world of cyberspace flourished and popular media resigned itself

to the slickness of MTV, a growing number of artists and designers began to

rebel against the ubiquity and singularity of mass production and digital

technology.

With the current boundaries

of technology being constantly pushed the revival of craft is a natural

rebellion. With the rise of knitting occurring with the movement it became a

chosen media for many contemporary artists. However the reaction of feminism

changed the craft from the 1960s, with women fighting for equality and change

many stopped knitting to protest the dreary symbol history had deemed it. Williamson

(1988, p25) states

Feminist thought has

been increasingly to intervene and try to change symbols, to engage in struggle

within the symbolic, and precisely to understand how our bodies and our images

are used as part of a network of social meanings.

Acknowledging the semiotics

of women and their general portrayal through time had to be changed in order to

gain equality with men. With the stereotype of the knitter falling into a

derogative social cast the dynamics of modern living had shifted and craft

became less popular.

The Arts and Crafts movement changed art by the use of

its aesthetics, politics and crediting all those associated with the production

of a piece, however the movement was predominately male influenced.

Contemporary art sees a turn with women investigating and creating new meanings

for craft in art, challenging stereotypes and traditions, and certainly

celebrating the rise of feminism. Knitting was re-born in terms of its context,

explored as a medium of art rather than a domestic craft. Before the new wave of

craft artists explored textiles within their work, however throughout modern

art the use of knitting does show evidence of irony. The 1970s and 80s saw

Elaine Reichek’s conceptual work which Marter (1978) depicts as ‘complex

pictorial systems with personal experience’, a formal series exploring knitting

as a traditional woman’s craft and coding it as a problem for the artist to

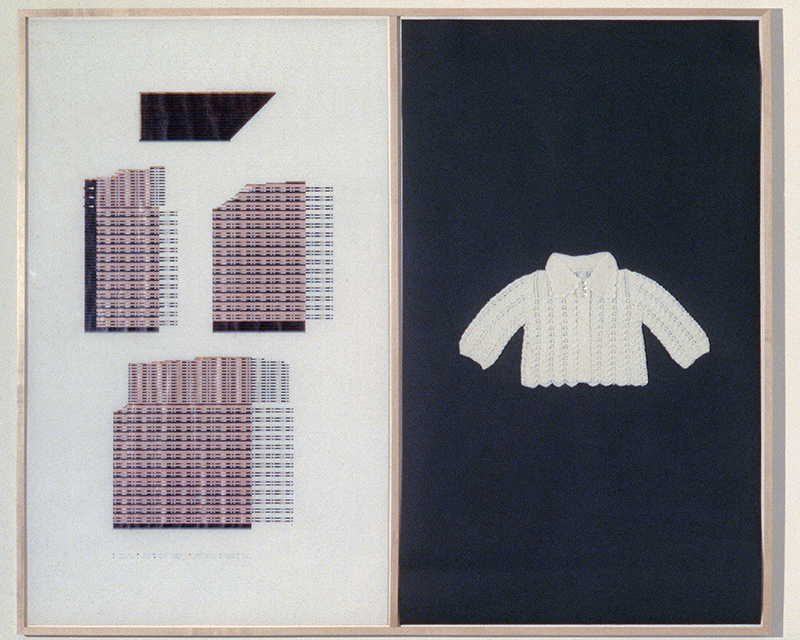

conceive and solve. Fig. 2, Laura’s Layette, is an example of how Reichek

investigates the process of the craft; the two-panel piece features a child’s

sweater, a graph drawing of the mechanical process on how to make it and a hand

knitting instruction booklet. Marter (1978) writes

Reichek focuses

attention on the formal patterning of our modes of operating in both knitting

and in ‘family’ life, as for example, what we believe symbolises our archetypal

home and mother,

by deconstructing the

rituals of families and knitting Reichek changes the concept of the craft, it

is no longer a domestic practice. The link to motherhood through the choice of

the child’s sweater gives the piece a feminist value, under Williams’s notion

it changes the typical view of the task of knitting by show casing it as a

method to make art. By undermining its practical values and showcasing it as

conceptual art Reichek changed the perceptions of knitting, allowing contemporary

artists to develop upon the principle she established through this body of

work.

|

| Fig. 2 |

The artists in the new wave of craft exploit knitting as

a medium for making political and personal statements, from Barb Hunt’s ‘Antipersonnel’

series on war to Margi Geerlinks contrast of digital manipulation with the

handmade in ‘Crafting Humanity’, craft’s changes its meaning to suit the maker

and viewer. Whether the artists state their works to be feminist or not their

use of craft does reflect feminist art theory. Meskimmon (2002, p381) writes

Feminists do not seek

to find a ‘new’ language or an ideal theory (‘untainted’ by contact with

‘phallogocentric’ discourses), but instead focus on the ways in which the

texts, objects, images and ideas which surrounded and interpellate us as

subjects might be reworked towards different ends.

Considering knitting in the

terms of Meskimmon’s writings contemporary artists such as Hunt do appear to

use feminism as a tool to aid their art practice. The Antipersonnel series is

made up of knitted replicas of land mines, life sized and in varied shades of

pink; the work incorporates the themes of tradition and death. Considering William’s

writings and the intent to change symbolic values in society Hunt successful

does this. During times of war women would knit socks to send to support the

troops, yet by using the same craft in the form of weaponry Hunt changes the meaning

from a soft thoughtful form of help to a political message on the welfare of

soldiers. The contrast in the subject and materials used allows a new

perception of knitting, the pink, a very human colour, could connote a

similarity to organs, and the slow process of hand making is much like human

growth which, in reality, is

quickly ended by the content of the pieces. Hunt, B (2007, p90) states ‘knitting has traditionally been used to make garments that protect and warm the body, quite the opposite of land mines, which destroy the body’, acknowledging the soft texture of knitting and the frailness of human life, the pieces demonstrate the value of life. Shauna Richardson’s crochetdermy uses the same principle of representing the themes of death, replicating taxidermy animals using craft. The reasons behind the work fall into the Dada practice that anything can be art, pushing art theory, ‘if anything can be art why not crochet? Realism? Highly accessible themes such as animals?’ writes Yin-Wong quoting Richardson (2010). Like Reichek, Richardson is taking craft into another realm, different to domestication. Like Hunt, she considered the medium because of its traditions, Richardson testifies that ‘crochet being an endangered craft in this country fits nicely in the concept’, relating to the feminist dismissal of what it symbolised and the revival to change the meaning of craft.

quickly ended by the content of the pieces. Hunt, B (2007, p90) states ‘knitting has traditionally been used to make garments that protect and warm the body, quite the opposite of land mines, which destroy the body’, acknowledging the soft texture of knitting and the frailness of human life, the pieces demonstrate the value of life. Shauna Richardson’s crochetdermy uses the same principle of representing the themes of death, replicating taxidermy animals using craft. The reasons behind the work fall into the Dada practice that anything can be art, pushing art theory, ‘if anything can be art why not crochet? Realism? Highly accessible themes such as animals?’ writes Yin-Wong quoting Richardson (2010). Like Reichek, Richardson is taking craft into another realm, different to domestication. Like Hunt, she considered the medium because of its traditions, Richardson testifies that ‘crochet being an endangered craft in this country fits nicely in the concept’, relating to the feminist dismissal of what it symbolised and the revival to change the meaning of craft.

|

| Fig. 3 |

With art and craft constantly developing with and against

technology representation also changes. Reichek work considers knitting in a

personal but formal structure, Hunt and Richardson produce intimate pieces,

which subtly shock the viewer through their semiotic discourse. Contemporary

artists mimic the values of the Arts and Crafts movement, rejoicing the individualism

in their work. Margi Geerlinks further challenges the notions of craft in art.

The Crafting Humanity series focuses on the human body and issues of

individualism, confronting the relationship of the handmade and digital

manipulation throughout the series. Fig. 6 deals with the theme of creation,

with the mother, the knitter, and the child who is inevitably the product of

the craft. Padovani and Whittaker (2010, p11) write how ‘the art of creation, rendered inert by the

photograph, appears here more self-driven than a selfless act of life giving’ realising the

image as cold and not typical of the craft. Geerlinks use of digital

manipulation in the image changes the content. The slowness of the craft

juxtaposes the digital world and technology, a twisted nostalgia. ‘By merging art and craft, concept and function,

this work and other like it, challenge the convention of knitting’ Padovani and

Whittaker (2010, p11) write, showing how not only does this challenge women’s

traditional role, it challenges the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement,

incorporating digital technology with the notion of the handmade.

|

| Fig. 4 |

|

| Fig. 5 |

Through investigating the Arts and Crafts movement and contemporary

art’s reflections upon it, knitting has been incorporated into art as a stable

and significant medium. The meaning of the craft in general leads back to the

feminist discouragement of home and hand making and the rise of women using

knitting in an ironic way. Although the work examined all feature different

discourse surrounding their content a feminist viewpoint is always established

which the viewer would relate to. Recognising the nostalgic quality of

knitting, the viewer, seeing it in a new form, will identify the change of the

handmade through the new wave of craft. Williamson and Meskimmon’s writings on feminism make it clear that

through the change of symbolism craft’s meaning suits the protest on equality,

with the gender stereotype on knitters being lifted.

Craft

in Contemporary Advertising

The rise of craft in art enables a huge following in culture, with many

people returning to hand making and DIY projects. With online social networking

sites such as Ravelry.com and buying and selling sites such as Etsy.com the

community of crafters is growing worldwide, sharing patterns and products. ‘Culture depends on its participants interpreting

meaningfully what is happening around the, and ‘making sense’ of the world’

Hall (1997, p 2) writes, the knitting culture therefore differs greatly to the

perceptions the outside world has on it, the current knitting societies

understand terms and thinking in a similar way, whilst outsiders only form opinions

on stereotypes. Mass culture is therefore targeted more within advertising,

rather than the communities who are more knowledgeable in the sub-cultures

referenced. This proves that advertising hijacks ideas from art and trends in

culture and changes their values to appeal to a wider audience. Therefore the

adverts that feature knitting and other crafts do not follow the Arts and Craft

movement’s morals, but rather extort them to make money.

Binet and Field (2009)

state ‘The most effective advertisements of all are those with little or no

rational content’, referring to successful campaigns that use emotional content

to influence consumers to buy the product. Adverts like

Shreddies ‘Knitted by Nanas’ are successful as they follow this rule. Knitted

by Nanas features Shreddies, a Nestle branded cereal that is square shaped with

a woven texture, being hand knitted by grandmothers in a factory of comfy

chairs, Fig. 6. It could be perceived as a grandmother’s heaven, hours of

knitting with friends in a comfortable environment. The product bears no real

resemblance to a knitted item, but the association with the nanas lets the

viewer believe, if only for a second, Shreddies are not mass produced in

industrial factories but made with the love of a grandma. Williamson (1978,

P158) writes how;

our past and memory of the past, are confused with someone else’s (or nobody’s, since the ‘past’ in the picture is a total construct). We are shown a hazy, nostalgic picture and asked to ‘remember’ it as our past, and simultaneously, to construct it through buying/consuming the product.

|

| Fig. 6 |

This denotes how adverts that use nostalgia work; the Shreddies advert uses a universal stereotype of the familiar, our grandmothers, allowing the audience to relate to the fictional characters. By purchasing the product the consumer becomes closer to these characters, the same closeness as wearing a wooly jumper made by a grandmother. The loose associating with the physical identity of the product and the constructed concept of how it is made uses Williamsons theory to entice viewers to buy the product. However the truth behind the product, the mass production, was one of the reasons for rebellion in the arts and crafts movement, and the new wave of craft. The stereotype of the knitter is used; the semiotics that the art of Morris and Co, Reichek, Hunt, Richardson and Geerlinks all play against is instead reinforced. Because the viewer can identify with the pigeonholed character the advert becomes successful, ‘connotation is the arbitrary in that the meanings brought to the image are based on rules or conventions that the reader has learnt’ Crow (2010, p55) writes, reinforcing how by using the typical image of the knitter more products are sold.

|

| Fig. 7 |

|

| Fig 8. |

The

recent 2011 Sudafed advert again coins knitting to promote another

mass-produced product. Here stop motion is used to convey an ill character and

the science behind the medicine, showing a detailed knitted view of the inside

of her head, Fig. 7. The phrase ‘wooly headed’ is used, which the advert plays

up to with the use of knitting, its discourse uses the concept that knitted

objects are things of comfort, intended to protect, just as the product does.

Like Hunt’s Antipersonnel series the viewer knows a substantial amount of time

has been taken to knit the pieces, however here the obvious is being used.

Rather than changing the meaning of the craft, it reflects on the known for

success. Barthes’ ‘Rhetoric of the Image’ examines a Panzani advert, writing

how its use of the familiar in culture is used.

The composition of the

image, evoking the memory of innumerable alimentary paintings, send us to an

aesthetic signified: the ‘nature morte’ or, as it is better expressed in other

languages, the ‘still life’; the knowledge on which this sign depends is

heavily cultural.

Barthes (1977, p69) states how the advert is constructed to induce an association with the past. Sudafed, like Nestle, are channelling a memory. Although the Sudafed advert is very simplistic and modern because of its reference to knitting it enables a connection with the past. The character used in the advert resembles a middle-aged woman, Fig. 8, which would be the target audience of the product, allowing it to be relatable without using a low budget actor. The relationship between the product and the concept of the advert does have more ‘rationale’ than the Shreddies advert, the target audience is less broad, however the women it is aimed at are in the age group who would stereotypically be knitting again, or be able to relate the craft to their mothers, showing a well thought campaign. However the company is only using the craft because of the recent trend in knitting. Because it is a recent advertisement it proves that the knowledge of the rise of craft in art has had a knock on affect in advertising, taking in only its aesthetics.

|

| Fig. 9 |

Like the Sudafed advert, Natural Gas use the stop motion technique, however on a much grander scale. Covering every aspect of a house in wool, Fig. 9, it gives the impression by using their heating you would be as snug as you would be in a handmade jumper. The production value of this advert reflects the time gone into the making of a jumper. Again using the idea that the knitted object is soft and warm. The biggest selling part of this service is the promise that will you feel not only warm and comfortable, but feel something real, a connection to the past through the tradition of knitting. Reflecting on a Kraft peanut butter advert Williamson (1978, p159) writes ‘we are given a false place in an imaginary time by the movement between past and future’ explaining how, because the advert features a recipe to make a cake with the product it places the viewer between when the advert is set and the future notion of making the cake. Natural Gas emulates this, despite it being fairly recent, it places the viewer in a mind set, between the past – the tradition of knitting and it’s associations, now – watching the advert, and the future – turning on the heating to fully experience what is being seen ‘now’. In reality the advert is just using knitting to sell their service, the name Natural Gas seems innocent, earthly and friendly, however ultimately its aim is to sell, feeding on our memories to make the consumer buy into it’s brand. Considering Williams writings, the Shreddies, Sudafed and Natural Gas all use nostalgia to connect with the viewer. Using emotional advertising techniques consumers reflect on cultural stereotypes and traditions to produce meaning within the adverts. Crow (2010, p55) writes ‘connotation is the arbitrary in that the meanings brought to the image are based on rules or conventions that the reader has learnt’, stating that for advertisements to exist and be successful they must rely on mass culture’s knowledge of the subject. The final example proves how ultimately advertising will always steal from art and culture to mislead the consumer into purchasing these products.

|

| Fig. 10 |

Smirnoff’s

‘Classic Mixed Drinks, In a Can’ adverts use the slogan ‘Yes You Can’ in a

number of scenarios, knitting being one of them. Featuring two male, hipster

characters, one asks “can you drink Smirnoff and Cola while knitting an

initiative set of leisurewear for your best friend?” takes a sip of the product

and then answers “yes you can”. The advert takes knitting in advertising

another step further, Sudafed realises the rise in knitting and takes advantage

of the generalised age range of women interest in craft, Smirnoff aim for a

much younger audience. By stereotyping a hipster as somebody who likes things

ironically, knitting is given a whole new meaning. It almost becomes the ultimate feminist aim,

placing a man in a typical women’s past time to sell a generic female drink.

The advert, like the conceptual artists using craft as medium, does so

ironically. It challenges men to accept equality, in the traditional culture.

If a man can knit then he can also drink a can of Smirnoff without social stigma.

Despite the advert being a forward step for the views on knitting it does still

conform to Crow, Barthes and Williamson’s writings on advertising. Its

semiotics relate to the current trends, obsessed with the past, vintage

apparel, furniture and music. It also relates to the new perceptions of men,

the use of the pugs show how its indented audience would be okay with their

feminine side.

The meaning of craft

in this advert is to sell, to reach the masses and encourage them to buy a

product that is not handmade. The use of knitting gives the sense, like with

the other adverts, that the products are made with care. Although the Smirnoff

advert is slightly different, it ultimately proves that advertising will steal

from the latest trends. Through exploring the Arts and Crafts movement the

knowledge of what the handmade should consist of becomes clear, Morris’

principles developed a new form of art, an art for the people, establishing

craftsmen and women as artists. The new wave of craft shows contemporary

artists and their uses of meanings and signs within art, as a rebellion against

the digital world it reflects the history of the Arts and Crafts movement. The

meaning of craft, primarily knitting, is developed by the artists that use and

explore it, it will always relate to feminist theory because of its history,

using irony to make political and personal statements. The meaning of craft in

advertising, however, does not reflect upon the principles of the Arts and

Crafts movement. As the handmade will always be about the individuality of the

product and the physical human flaws seen on the pieces, mass production can

never reproduce this. Advertising will borrow for all genres, its intent only

to sell. Advertising knows its target market. The use of craft in advertising

is intended for mass culture, Shreddie’s use of the ‘iconic’ traditional

knitter proves nostalgia is exploited, Sudafed and Natural Gas both use

knitting, like Hunt, to express care in production, and Smirnoff reflects upon

the craft in an ironic fashion. In conclusion despite adverts appearing as if

using the handmade for ‘good’, ultimately they will never reflect on the true

meaning of craft in art, only imitate it to make sales.

Fig. 1

Morris, W, Morris & Co, Jeffery. Blackthorn. (1892). [Online Image].

Available from: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O250943/wallpaper-blackthorn/

[Accessed 4 January 2012]

Fig. 2

Reichek, E. Laura’s Sweater. (1979). [Online Image]. Available from:

http://www.elainereichek.com/Project_Pages/16_EarlyKnit/LaurasSweater.htm

[Accessed 12 January 2012]

Fig. 3

Hunt, B. Antipersonnel

– detailed landscape. (n.d.). [Online Image]. Available from: http://www.barbhunt.com/

[Accessed 12 January 2012]

Fig. 4

Richardson, S. Crochetdermy Deer. (n.d.). [Online Image]. Available from:

http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/gallery/22/6452/5/crochetdermy

[Accessed 12 January 2012]

Fig. 5

Geerlinks, M. Crafting Humanity – woman knitting. [Online Image]. Available from:

http://www.margigeerlinks.com/ [Accessed 15 January 2012]

Fig. 6

PassionateGuinevere. (2007). Shreddies – Knitted by Nanas. [online].

Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lRuiQrpXpG0 [Accessed 15 January

2012]

Fig. 7

Sudafeduk. (2011). Offical New SUDAFED TV Advert. [online]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I5BEAxOdA0c

[Accessed 15 January 2012]

Fig. 8

Sudafeduk. (2011). Offical New SUDAFED TV Advert. [online]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I5BEAxOdA0c

[Accessed 15 January 2012]

Fig. 9

HQSAVE. (2010). Natural Gas: Warm Comerical, a best commercial TV Ads. [online].

Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ukOyklWOUXw&feature=related

[Accessed 15 January 2012]

Fig. 10

Yesyoucantv. (2011). Smirnoff and cola: Knitting. Yes you can. [online]. Available from:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EySKuCGZO6E&feature=related [Accessed 15

January 2012]

Bibliography

Anscombe, I. and Gere, C. (1987) Arts and Crafts in Britain and America.

London: Academy Editions

Binet, L and Field, P. (2009). Empirical

Generalizations about Advertising Campaign Success. Journal of Advertising Research. [online]. Available From: http://mediablog.typepad.com/files/empirical-generalizations-about-advertising-campaign-success-1.pdf

[Accessed 2 January 2012]

Barthes, R. (1977). The Rhetoric of the

Image. In: Hall, S. (eds.) Representation: Cultural Representations and

Signifying Practices. London: The Open University

Crow, D (2010). Visible Signs: An Introduction to Semiotics in the Visual Arts.

London: AVA

Greensted, M. (2005) An Anthology of the Arts and Crafts Movement: Writings by Ashbee,

Lethaby, Gimson and their Contemporaries. Hampshire: Lund Humphries

Hardy-Moffat, M. (n.d.).

Feminism and the Art of “Craftivism”: Knitting for Social Change Under the

Principles of The Arts and Crafts Movement. Concordia

Undergraduate Journal of Art History. [online]. Available from:

http://art-history.concordia.ca/cujah/essay3.html [Accessed 12 December 2010]

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural

Representations and Signifying Practices. London: The Open University

Hung, S. and Magliaro, J. (2007) By Hand: The Use of Craft in Contemporary

Art. New York: Princeton Architectural Press

Hunt, B. Barb Hunt. (2007) In: Hung, S. and

Magliaro, J. (eds.). By Hand: The Use of

Craft in Contemporary Art. New York: Princeton Architectural Press

Marter, J. (1978). Elaine Reichek. Arts Magazine. [online]. Available from:

http://www.elainereichek.com/Press.htm [Accessed 2 January 2012]

Meskimmon, M. Feminisms and Art Theory.

(2002). In: Smith, P and Wilde, C (eds.). A

Companion to Art Theory. Oxford: Blackwell

Padovani, C. and Whittaker, P. (2010).

Twists, Knots and Holes: Collecting, the Gaze and Knitting the Impossible. In:

Hemmings, J. (ed.) In the Loop: Knitting

Now. London: Black Dog Publishing. pp. 10-17.

Wagner, A. Craft: It’s What You Make of It.

(2008). In: Levine, F. and Heimerl, C. (eds.).

Handmade Nation: The Rise of DIY,

Art, Craft and Design. New York: Princeton Architectural Press

Williamson, J. (1988). Consuming Passions: The Dynamics of Popular Culture. London: Boyars

Williamson, J. (1973). Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising.

Yin-Wong, F. (2010). Crochetdermy. Dazed Digital. [online]. Available from:

http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/6452/1/crochetdermy

[Accessed 2 January 2012]

That is very nice collective information about Craft mean Art. we can say Craft is Art.

ReplyDelete